Indiana is home to the third-largest Amish population in the United States. Also known as “Plain People”, the Amish and Mennonites, reside in numerous counties, where many of them farm. Traditionally, these communities refrain from using modern technology, yet many of their crops are mapped in DriftWatch™. Learn how the technology equity gap is being closed from an interview with Jeff Burbrink, Elkhart County Purdue Educator for Ag & Natural Resources and Beth Carter, Statewide Pesticide Investigator with the Indiana Office of the State Chemist and the Data Steward for the Indiana FieldWatch Registries to learn about this.

Could you give a brief history of how your work with the Amish / Mennonite/ Plain communities has changed over the years regarding the use of the FieldWatch registries?

Jeff:

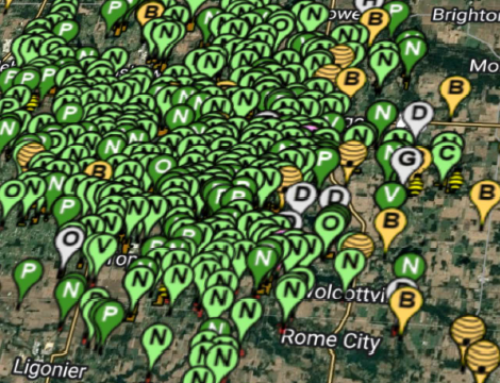

It all started a few years ago, in northern Indiana, with an outbreak of Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE), a mosquito-borne disease that affects humans and horses. To combat the virus, the state health department decided to spray insecticides over large swaths of land, which included considerable areas where our Amish and Mennonite settlements are. Many of those farms are small acreage and raise sensitive and/or organic crops. To prevent crop damage, more than 400 farms were plugged into DriftWatch in just a 2-3-day period, in the hope they would not be sprayed on by the planes. This happened for two consecutive years. In LaGrange County alone, there are currently 321 DriftWatch entries for Amish and Mennonite growers.

Beth:

In the beginning, some of the Plain community did not see the need and value in using the digital mapping on FieldWatch. Over time, they have come to accept and embrace FieldWatch. As Jeff referenced above, the need to map became critical for these sensitive crop producers and beekeepers in connection with the EEE spraying. Additionally, some pesticide labels require applicators to check the registry before spraying, which confirms the value of registering on FieldWatch. As more Plain growers became interested in mapping their sites, it has been imperative to have help from local extension educators. It has been no small undertaking to register all those users and I am very grateful for Extension.

Can you point to any specific ways in which FieldWatch has helped improve this process in recent years?

Jeff:

One challenge we face with this population is that they do not have email addresses, which are required for a DriftWatch entry. So, we created a “false” email address to plug into those entries. This year, we have decided to convert the false email address to the standard Purdue Extension generic email address, which means any email sent to them is deposited into our county Extension Office’s inbox. This has helped avoid bounce back emails to the DriftWatch administrator.

Beth:

As a data steward, I appreciate how FieldWatch has adapted to these changes and made the process more streamlined. I can now readily transfer site ownership. Additionally, I have the ability to create a ‘super user,’ so Extension agents like Jeff can maintain hundreds of growers under one account.

Have you been able to share some of how you serve these communities with others across the US? If so, what has allowed this to happen?

Jeff:

In November 2022, there was a national conference held in northern Indiana for agencies who work with Plain Communities. We talked about our DriftWatch experience there.

Is there anything you would like to share to encourage the readers to better serve their communities by bridging the technology equity gap?

Jeff:

Renewal time is difficult. The standard way that the renewals have been processed is by setting up a booth at an Amish focused conference each winter. In 2024, there were 2,375 people in attendance. However, only about 30 farms out of 321 renewed their sites over the

two-day time frame, leaving more than 290 entries to expire come March. Of the 30 farms that renewed, about 20% had changes to property lines, whether it be from selloffs, additions, or other boundary changes. Extrapolating, that could mean that 60 or more of the 321 farms in the database need to have their data adjusted. Simply hitting the ‘renew’ button will leave the database compromised. Automatically renewing sites without adjustments two years in a row could lead to almost 1/3 of the DriftWatch entries becoming incorrect.

It has been proposed that Plain organic growers work with their organic certifiers to update their registry entries, since they must work with the certifiers several times a year to maintain their organic status with the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). The certifiers are privy to the boundary changes, land additions, and property sell offs, while Extension Offices are not part of that communications loop. Including DriftWatch mapping into the services offered by the certifiers would result in a much cleaner and more accurate

database.

The other challenge is mapping the properties. The home address entered in the registry is not necessarily the address of the field. It is much better to have the grower looking over your shoulder while mapping out boundaries. Attempting to map property boundary changes over the phone or adjust for property sales or additions without the farmer in the room is a recipe for inaccurate records. Since coming to an Extension Office with a horse and buggy can be time consuming, it makes sense for the growers to work with their certifier, who visits their farms on a regular basis.

Beth:

The Plain community serves an important role in growing many of our specialty and sensitive crops in Indiana. Applicators don’t always know where these crops and managed bee hives are located. The Extension Office has been pivotal in reaching and registering this tech cautious group. Having relationships with their Plain community, it is easier for Extension to gain local acceptance. When they can get Plain farms registered on FieldWatch, we help to bridge the gap and foster communication. Applicators and sensitive crop producers both have equally important jobs. When we work together to avoid drift and/ or negative impacts to neighboring farms, we all win.